Young Belgium, Opus I - Ineffable, 13.12.2020 - 27.02.2021

Léa Belooussovitch, Pierre-Laurent Cassière, Hannah De Corte, João Freitas, Alice Leens, Sahar Saâdaoui

La Patinoire Royale - Galerie Valérie Bach, Brussels, Belgium

Exhibition view, Young Belgium, Opus I - Ineffable, 13.12.2020 - 27.02.2021, La Patinoire Royale - Galerie Valérie Bach, Brussels, Belgium | © Gilles Ribero, REGULAR STUDIO

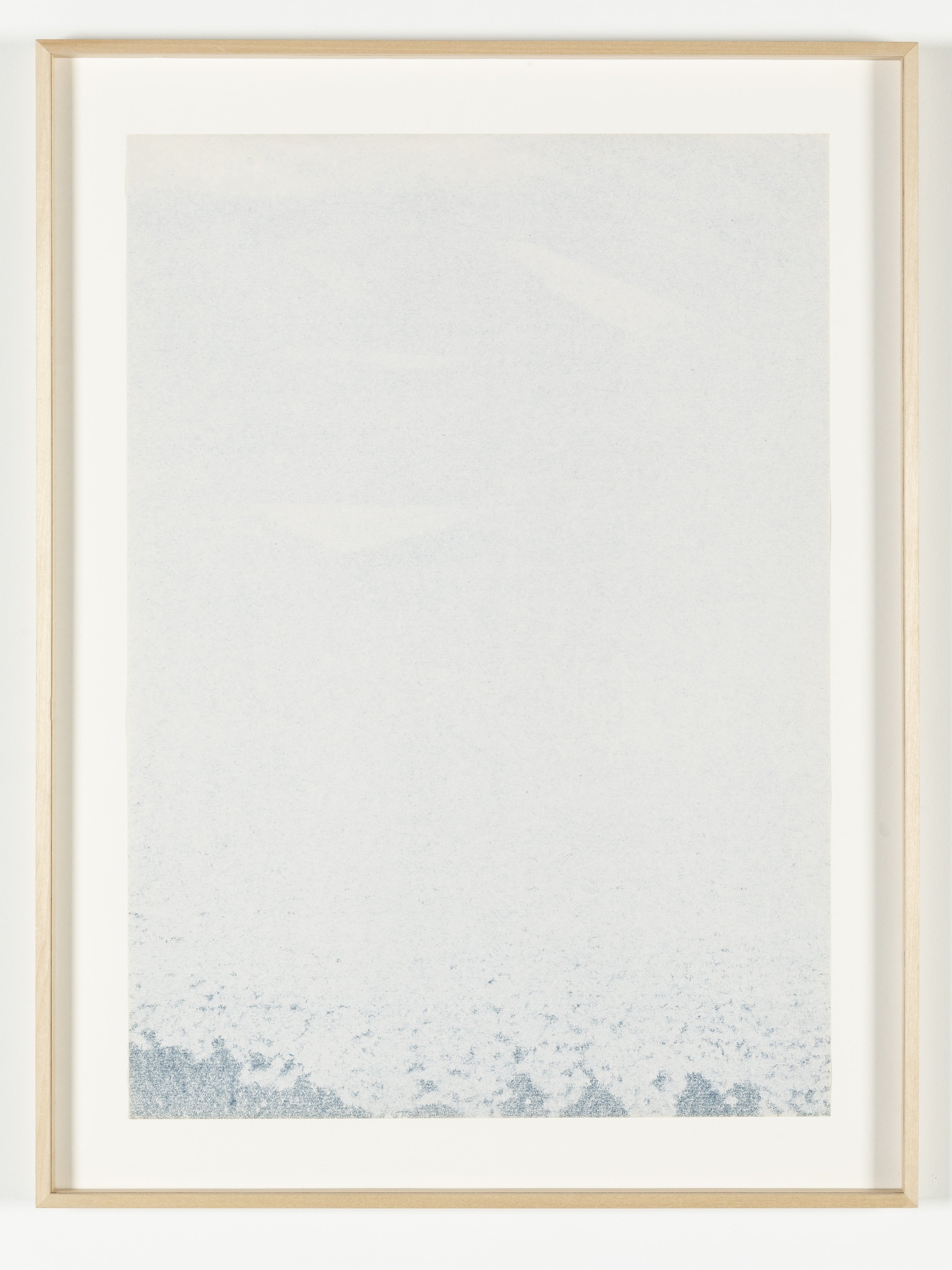

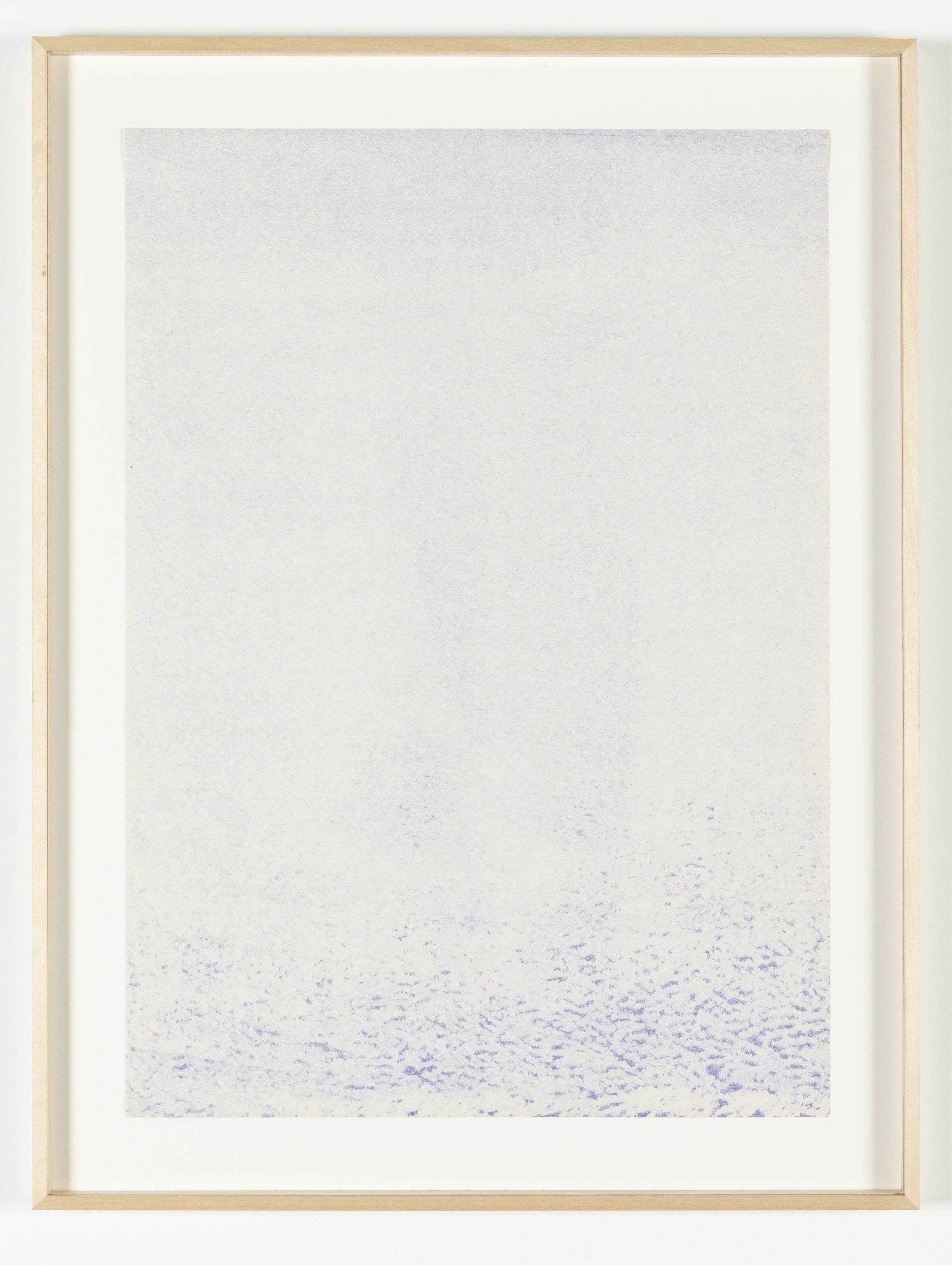

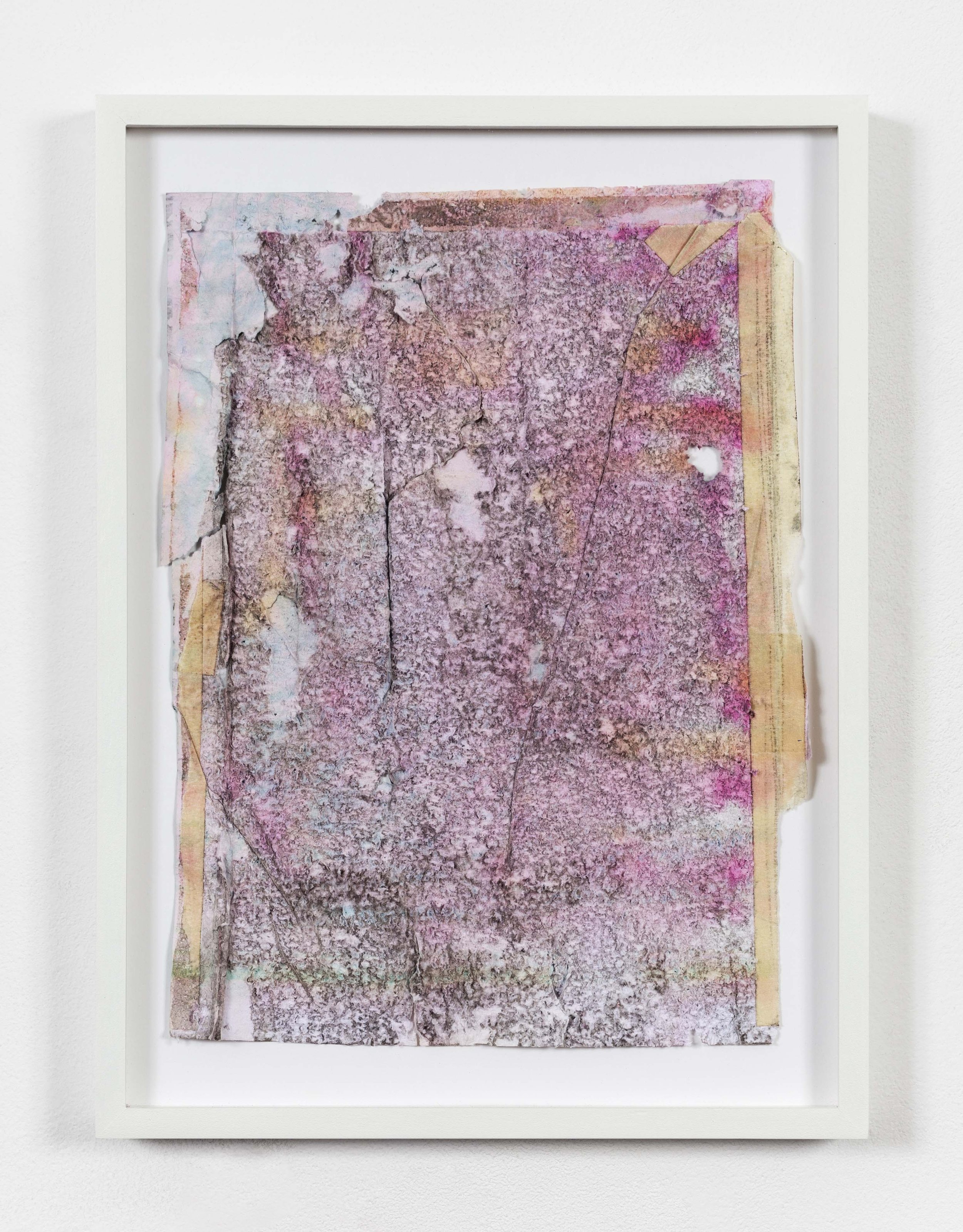

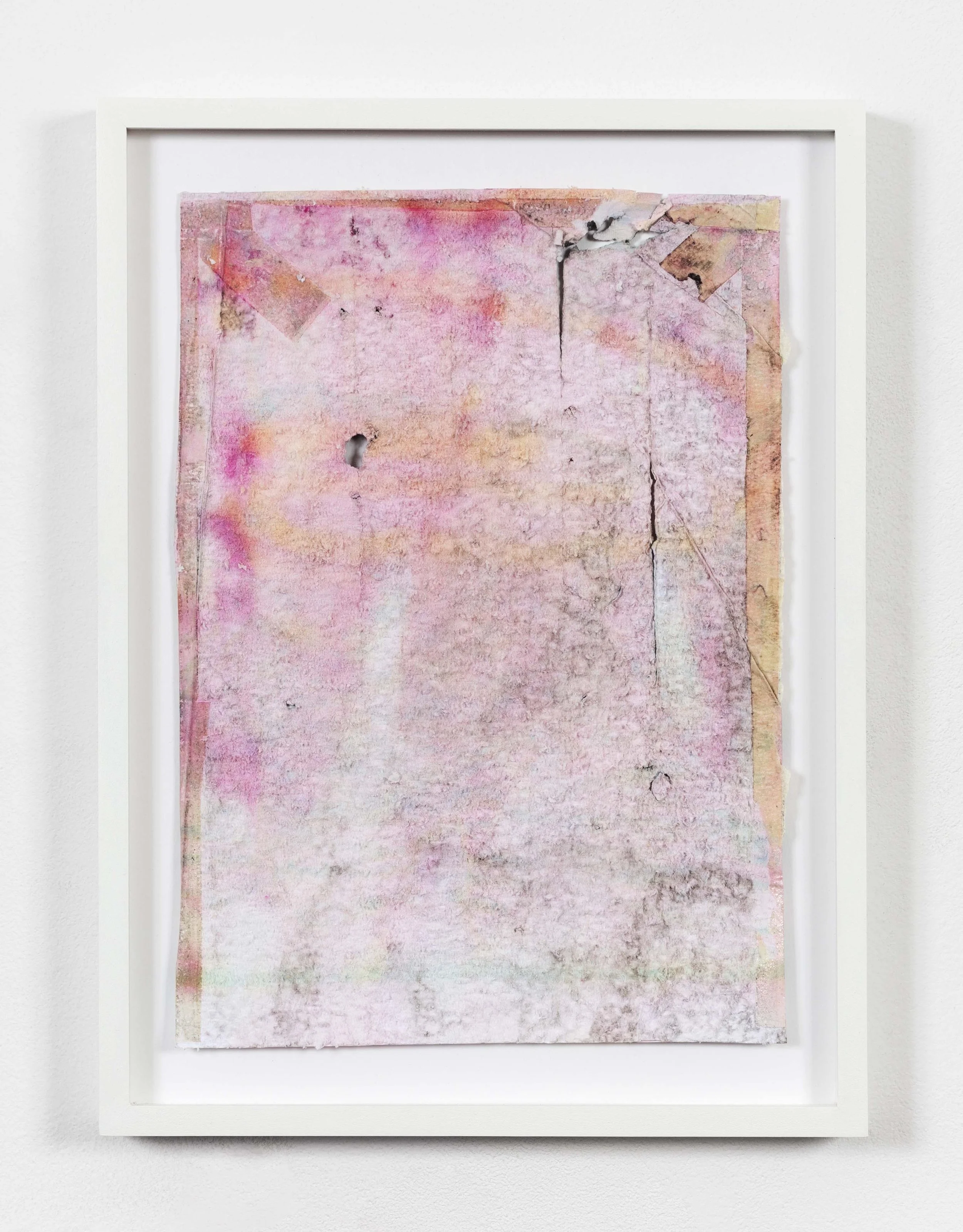

Untitled (Mother of pearl I, II & III), 2020 — Iridescent paper (peeled off) — 83 x 62,5 cm (each)

Untitled, 2020 — Tetra pak cardboard protection (heated & peeled off) — 174 x 120 cm

Untitled (Network I), 2018 — Tetra pak cardboard protection (heated) — 113 x 93 cm

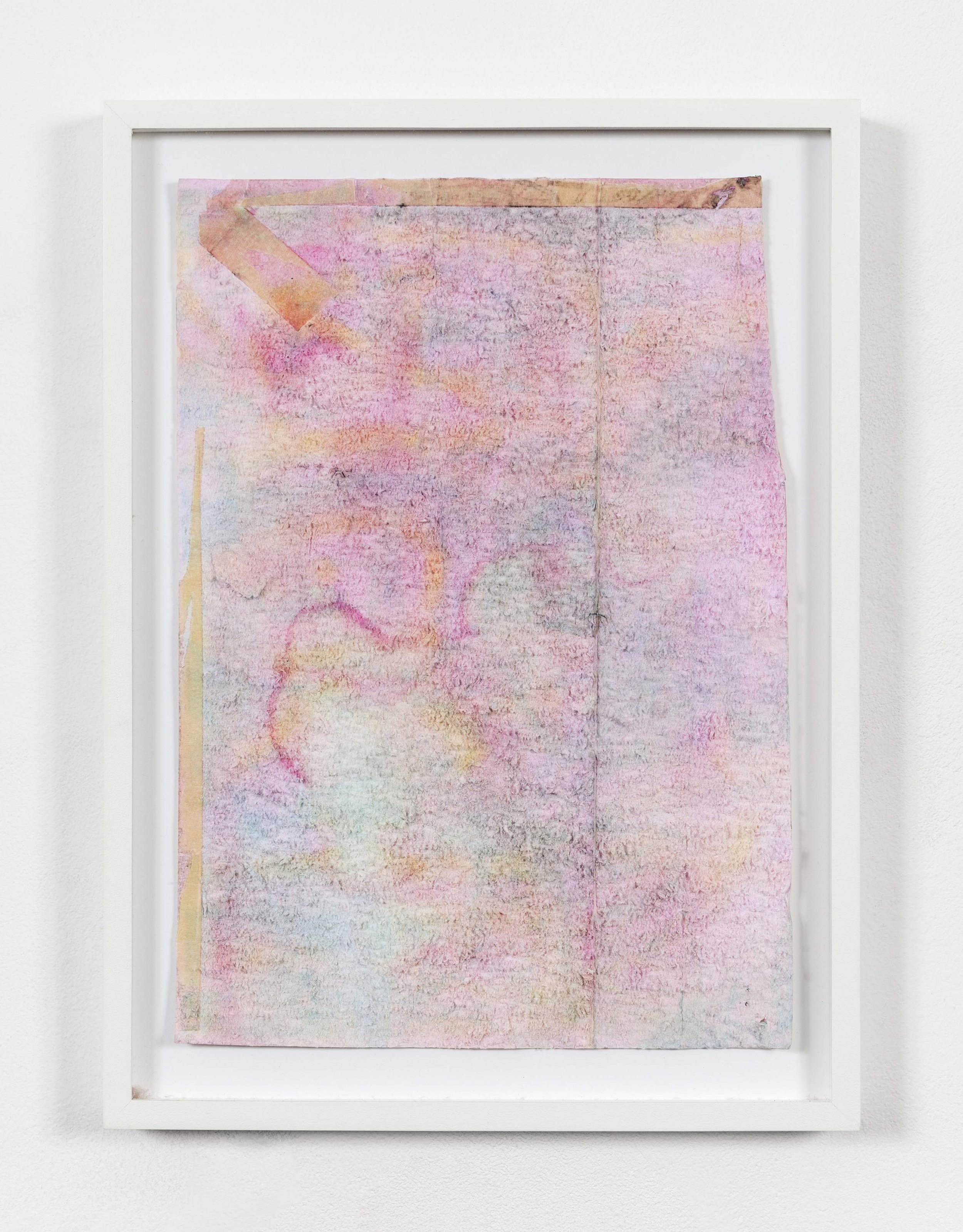

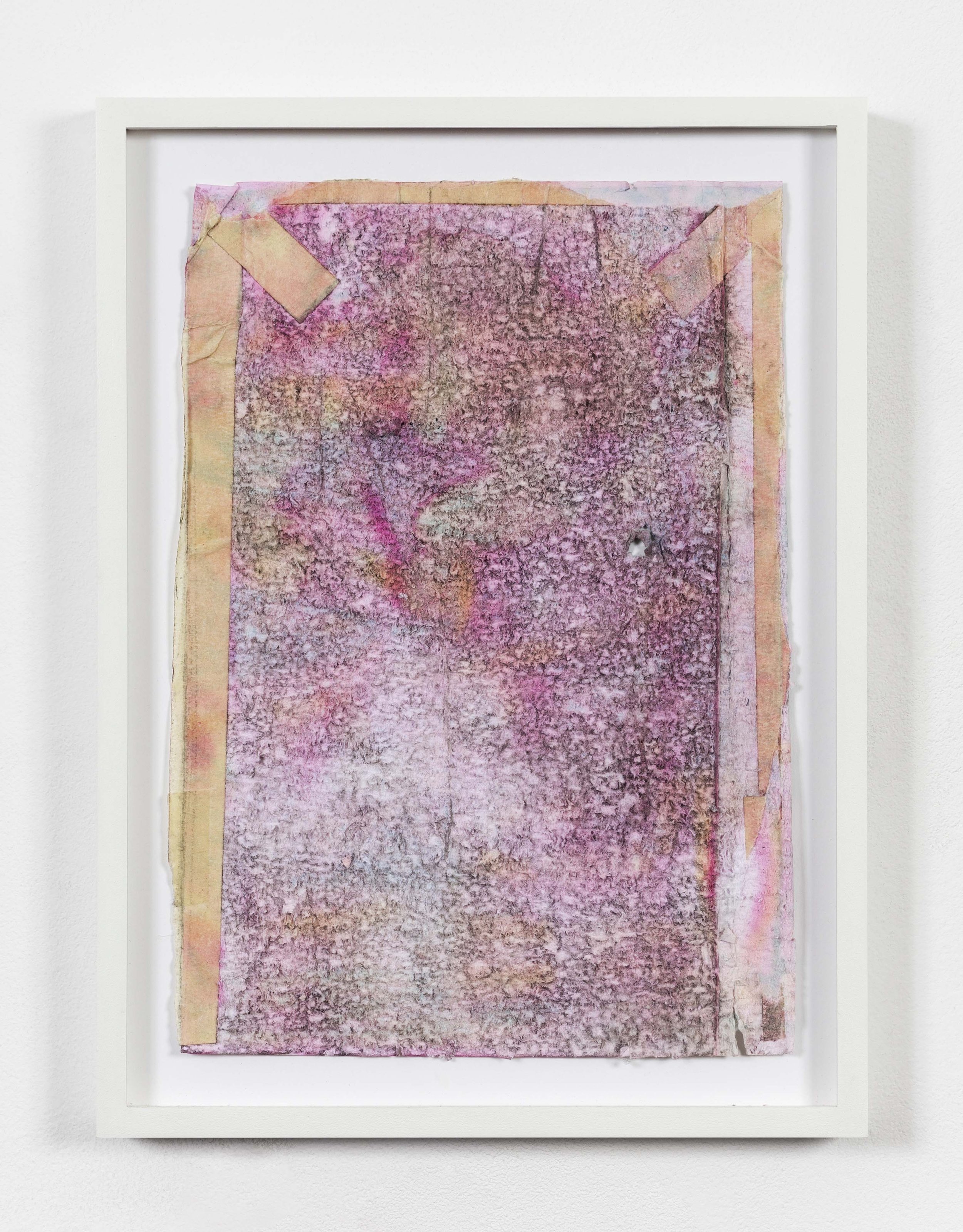

Don’t you fade away, 2017 — Found poster, rain, residues (fragmented & scratched) — set of eight frames, each 35 x 26 cm

Partition III, 2019 — Hospital cotton cloth, thread, canvas (cut, sewn & stretched) — 210 x 165 cm

Untitled (Inside out), 2020 - present — Found envelopes mounted on aluminium — Variable dimensions

Untitled (Frühlingsstimmen), 2020 — Exhibition poster (sanded) — 180 x 120 cm

Untitled (Transcription I - V), 2019 — Pencil, newspaper ink, paper, wood, paint, glass — 36,2 x 25,7 x 2,2 cm (each)

Untitled (La gazetta dello sport), 2018 — Pencil, newspaper — 91 x 66 cm

Autopsie d’un palimpseste

Le travail de João Freitas est en lien avec la notion de trace, d’usure, de temps, traitant tels des écorchés les structures qui lui servent de support : papiers, cartons, tissus, papiers de verre, bois, etc..., l’intention de l’artiste étant de violenter doucement la matière pour lui faire dire, avouer quelque chose d’insaisissable, comme une planche d’anatomie dévoile les véritables structures et composantes d’un organisme.

Il y a chez Freitas une volonté de révéler, de soulever la matière, de lui donner un sens mystique par la révélation de ses arcanes et de ses mutations, comme le travail de l’alchimiste transmute les matières en éthers, vapeurs et autres essences.

João Freitas est de ces artistes qui apprennent de leur propre travail. Rien ne semble décidé au départ de ses dissections ; il trouve en cherchant, tel un archéologue qui dégage l’objet enfoui. En esthète apprenti, sensible et attentif, il cherche dans ces artefacts des combinatoires illimitées d’effets et de jeux, générant une infinie poésie qui n’exclut pas la violence. Et à ce titre, dans ce rapport tout à la fois brutal et suave à la matière, il arrive à nous faire entrer en résonance avec ces ineffables questions de temps, de tangible, de présence, devenant dans son creuset, une matière durable, touchante et immanente.

Que ce soit par l’usure, le ponçage ou le brûlage, le pli, le cousu, le froissé, il révèle la matière en la faisant accéder à une transcendance, via une chirurgie qui, sans la trahir, fait renaître le support dans une autre dimension. C’est le sens ineffable du travail de João. Telle une pellicule photographique, tel un sgraffite ou une ‘carte à gratter’, telle une pelure, il révèle le réel par un travail répétitif, quasi méditatif, d’enlèvement, de dépeçage, d’arrachage, de griffure, qui fait apparaître la réalité sous-jacente, dans une démarche proche du nouveau matiérisme, qui se saisit des questions de durabilité, de gratuit, de récupération et de réenchantement. Sa démonstration est celle d’un thaumaturge, d’un sorcier qui révèle la vraie nature du monde, le met à nu, pour en montrer l’indevinable constitution.

Extatique expérience que cette nouvelle compréhension du réel, face à ces tableaux de peaux brûlées, de membranes meurtries, de tissus suturés, ... qui donne à voir en vrai une souffrance appliquée à la nature inanimée des matières, qui par cette douleur apparente semblent prendre vie.

Nous parlons de l’autopsie d’un palimpseste comme métaphore à notre sens parfaite du travail de João : le palimpseste est un parchemin (fait de peau d’animal) qui a été gratté sur toute sa surface pour en faire disparaître une première écriture, afin d’y écrire un nouveau texte. C’est absolument de réécriture dont il est question dans l’œuvre de l’artiste : par son geste, quel qu’il soit, il efface la première version de la matière ou du message, afin d’y inscrire une nouvelle réalité, de faire apparaître une deuxième version d’un même support. Et ce travail d’artiste, qui s’apparente à une autopsie de la mort, mort à la première version de la matière, est enrichie par le hasard du résultat, qui s’allie avec la volonté de l’artiste de donner à saisir une nouvelle formulation du monde.

C’est en ce sens que la transfiguration de l’œuvre participe à cette autre lecture du réel, qui nous invite à trouver dans ses manifestations d’autres émotions, d’autres possibles, d’autres ravissements.

Constantin Chariot

Soothed Entropy. On the Role of Frames in the Works of João Freitas.

You find yourself surrounded by encased materials, in what may appear to be a showcasing of (photographic) stills of textures. From the centre of an ensemble of vertical frames, the eye travels horizontally from one surface to the next, and vertically so as to explore each rectangle, each texture. Drawn to one surface, perhaps you approach it. There you encounter affected man-made, industrial materials. The processed and standardized materials have been degraded, often slowly and as evenly as possible. The materials are degraded to uplift them, wounded so as to attract attention to them, turning them into surfaces worthy of being framed, with the aim of “giving them a soul again,” as João puts it.

In the making, the materials and processes may be sculptural: they are floor-made; they involve carving and mass. Yet the frame returns the object to the primary intention that shaped it–that of drawing. Because (make no mistake) the issue at hand is drawing. It is the conductor of the work: materials are manipulated with line as a directive thought; the gesture is often linear...and always direct; the work is about imprint and crease; it can be said to be descriptive, and outlines and surface matter (as opposed, it seems, to mass).

At times the attack (in the musical sense: the quality of the impulse of an action) may stretch the mass-produced and rectangular objects out of shape, challenging the edges of the rectangle, but the frame calls it back in. All the while the frame emphasizes the slight deformations against its own straight lines. The transformative action is put to rest in the box-like structures and stilled by the thin (wooden) line surrounding the surface, a transition to the wall.

The making process breaks down the support itself, its skin and the layers it comprises. Hammer, torch, scraper and other instruments cut, crack, blow, dissolve... impacting the tissue of paper, wood and other materials. The materials’ natural process of ageing is accelerated through wilful, often delicate and controlled, gestures. Gestures are controlled, yet the composition is not: it emerges from the material. Tetra Pak sheets are burnt by moving a lighter across the surface from left to right, top to bottom, following the writing/reading direction. The lighter burns off layers, revealing the intricate structures of an everyday material. Glue that holds together sheets of wood or paper leaves colour where parts of the material have detached, deeply marking the surface, generating structures and patterns out of the material. Is it abstract? “No, though it is decorative and there are patterns, it is not abstract...it is very concrete. It is something of a trace... something of an expedition...something happened,” says João Freitas.

Consequently, one material can come in several states, as a witness of just one halt in the process, one stop in the expedition. Depending on the intensity of the technique and the depth of the gesture, which dictates the number of layers unearthed, a Tetra Pak sheet will appear black and aluminium in the first stage of the process, but brownish and orange in its final state.

Beyond their main protective role, and that of indicator of the medium, the frames are chosen to foster meaning: the linden wood borders of the Mother of Pearl series evoke the natural world beyond the landscape that the surfaces may present; an empty frame in Don’t you fade away tells the story of the disappearance of one of eight paper pieces of a poster, so soaked that it dissolved, serving in fact as an indication of how the whole series came to be; aluminium backings behind the coloured insides of envelopes (that carry the imprint of their other half) press the postal elements to the foreground; the stretcher frame of the striped hospital bed fabrics sewn together holds them in tension and organizes them into a music sheet...

The frames also halt the work at a certain moment of tension. A mise-en-scène of the natural process of decay is central to the work. It is feigned entropy, an intense acceleration of decay during the relatively short time of the making process (compared to the lifespan of the work) which is stopped not according to a protocol, but in accordance with the reactivity of the material. The acceleration of decay is even overturned when the material is framed, when the dissolution is (artificially) put to a halt... The frame installs tension between fragile forms in a state of dissolution and their protection and enshrinement. Forms destined to be discarded or lost (old envelopes about to be thrown out, street posters, ...) find another existence. Perhaps this attempt at halting through framing answers to the human desire–stronger than all others–to resist the dissolution of form.

As decay inevitably continues (though at an almost imperceptible pace) and small pieces detach from the work during various phases of its life (in transport, in storage and on display), the frames become the keepsakes of that: tiny pieces of aluminium skin and particles of paper dust accumulate at the bottom. The boxes of the frames keep every trace of the slow evolution. There is no loss of matter in the microcosm of the frame.

Hannah De Corte